Concepts¶

Contrast is a beamline interface based on IPython. The code is organized as a library containing various classes. A beamline is set up simply by making instances for detectors, motors, and any other devices directly in IPython or in a script.

Contrast conceptually does three things,

- Represents and keeps track of beamline components as python objects.

- Provides shorthand macros to do orchestrated operations on these devices.

- Keeps track of the environment in which the instrument is run.

The framework runs locally in an IPython interpreter. This allows simple interactions between all beamline components. Parallelization is avoided in the interest of simplicity, with the exception of the data handling/streaming/writing machinery, which would otherwise slow down the light-weight acquisition loop.

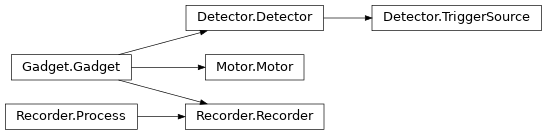

Gadget and its subclasses¶

Contrast classes which represent specific beamline components (hardware or software) inherit from the common Gadget base class. Its most important subclasses are Motor (primarily for affecting some aspect of reality), Detector (for measuring some facet of the universe) and Recorder (for saving or passing on gathered data).

Instead of keeping central registries or databases, Contrast keeps track of Gadget objects through instance tracking and inheritance. The base class or any of its children can report what instances of it exist, and calling the getinstances() method of classes at different levels serves to filter out the objects of interest. An example follows.

In [1]: [m.name for m in Motor.getinstances()]

Out[1]: ['gap', 'samy', 'samx']

In [2]: [d.name for d in Detector.getinstances()]

Out[2]: ['det1', 'det3', 'det2']

In [3]: [g.name for g in Gadget.getinstances()]

Out[3]: ['gap', 'detgrp', 'det1', 'samy', 'samx', 'det3', 'det2', 'hdf5recorder']

Motors¶

Classes which inherit Motor represent physical motors or other devices which can be represented by numerical values (a bias voltage or beam energy, perhaps). The Motor class defines a simple API for moving the motor and reading its position.

Motors have dial and user positions, where the dial position should correspond closely to the physical position of the underlying hardware. The user position can be set at runtime to meaningful values. For example, a microscope translation stage might be set to zero when focusing on a sample plane. The dial and user positions are related by a scaling factor and an offset, handled by the Motor base class. Motor limits are stored internally in dial positions, so that they remain physically identical after changing the user position. The motors module defines convenience macros for moving, listing and reading motors, as well as defining user positions.

Detectors¶

The Detector base class defines the API for classes representing all detectors and data collecting devices. To operate a detector, the methods prepare(), arm(), start() are called, with read() called after the acquisition has finished.

Detectors come in many forms, and the Detector objects can return data of any type. Usually, numbers, small arrays, or Python dict objects are used, as these are easily written to hdf5 files in a hierarchical way. Detectors which produce large data rates write directly to disk or stream their data to a receiver, and therefore return hdf5 links instead of real data.

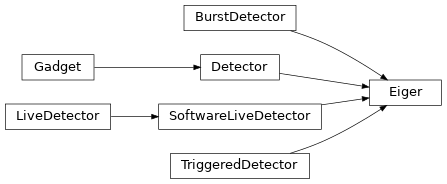

Variants of Detector can be constructed by inheriting the base classes for hardware-triggered detectors, those that can run autonomously in live mode, and those that can take bursts of measurements with internal timing. The inheritance structure for the Eiger subclass is shown below for illustration.

Recorders¶

Data is captured by recorders. Recorders are run in separate processes and get data through queues to avoid holding up the main acquisition loop. They can do anything with the data, for example saving to hdf5 files, live plotting, or streaming. See the Hdf5Recorder, PlotRecorder, and StreamRecorder classes for examples.

Note how easy it is to write these recorders, and how easy it would be to integrate online data analysis. The recorder simply grabs data from an incoming queue, while the data collection routine places collected data in the queues of all running recorders. As an example, here’s how SoftwareScan and its derivatives gather and distribute data.

# read detectors and motors

dt = time.time() - t0

dct = {'dt': dt}

for d in det_group:

dct[d.name] = d.read()

for m in self.motors:

dct[m.name] = m.position()

# pass data to recorders

for r in active_recorders():

r.queue.put(dct)

The lsrec macro lists currently running recorders.

In [30]: lsrec

name class

---------------------------------------------------------------------

hdf5recorder <class 'contrast.recorders.Hdf5Recorder.Hdf5Recorder'>

plot1 <class 'contrast.recorders.PlotRecorder.PlotRecorder'>

Macros¶

A macro is a short expression in command line syntax which can be directly run at the ipython prompt. The following is a macro.

mv samx 12.4

In this framework, macros are created by writing a class with certain properties and marking that class with a decorator. This registers the macro as a magic ipython command. All available macros are stored in a central list, and can be listed with the lsmac command. The macro syntax is similar to sardana and spec.

In [1]: import contrast

In [3]: %lsmac

name class

---------------------------------------------------------------

activate <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.Activate'>

ascan <class 'contrast.scans.AScan.AScan'>

ct <class 'contrast.scans.Scan.Ct'>

deactivate <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.Deactivate'>

dmesh <class 'contrast.scans.Mesh.DMesh'>

dscan <class 'contrast.scans.AScan.DScan'>

liveplot <class 'contrast.recorders.PlotRecorder.LivePlot'>

loopscan <class 'contrast.scans.Scan.LoopScan'>

lsdet <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.LsDet'>

lsm <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.LsM'>

lsmac <class 'contrast.environment.LsMac'>

lsrec <class 'contrast.recorders.Recorder.LsRec'>

lstrig <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.LsTrig'>

mesh <class 'contrast.scans.Mesh.Mesh'>

mv <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Mv'>

mvd <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Mvd'>

mvr <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Mvr'>

path <class 'contrast.environment.Path'>

setlim <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.SetLim'>

setpos <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.SetPos'>

spiralscan <class 'contrast.scans.Spiral.SpiralScan'>

startlive <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.StartLive'>

stoplive <class 'contrast.detectors.Detector.StopLive'>

tweak <class 'contrast.scans.Tweak.Tweak'>

umv <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Umv'>

umvr <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Umvr'>

userlevel <class 'contrast.environment.UserLevel'>

wa <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Wa'>

wm <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.Wm'>

wms <class 'contrast.motors.Motor.WmS'>

Do <macro-name>? (without <>) for more information.

Macros aren’t stored in a special library. They are written throughout the library wherever they make sense. For example, in Detector.py where the detector base classes are defined, the lsdet macro is defined as follows.

@macro

class LsDet(object):

def run(self):

dct = {d.name: d.__class__ for d in Detector.getinstances()}

print(utils.dict_to_table(dct, titles=('name', 'class')))

A macro is different from a script. Anyone can easily write a macro, but for composite operations where existing macros are just combined it is faster to write a script. The following is a script, not a macro, but uses a special runCommand function to interface with the command line syntax.

from contrast.environment import runCommand

for i in range(5):

runCommand('mv samy %d' % new_y_pos)

runCommand('ascan samx 0 1 5 .1')

The environment object¶

No global environment variables are used. Instead, a central object in the environment module is used to manage the overall logistics of the beamline. This includes things like paths and scan numbers:

In [24]: from contrast.environment import env

In [25]: env.nextScanID

Out[25]: 1

The central env object has the following attributes which relate to beamline configuration and behaviour.

| Attribute | Role |

|---|---|

nextScanID |

The scan number of the next acquisition. Updated by the acquisition macros. |

lastMacroResult |

Optionally, macro run() methods can return data. Any time a macro is run, its return data is stored here. |

userLevel |

The current user level limits what motors can be moved and listed. See the section on Usage. |

paths |

A PathFixer object, which manages data paths. By default, this object simple takes the data path as an attribute, but custom subclasses can be written which grab the path from other parts of the controls system, like at NanoMAX. |

scheduler |

An object which is able to tell (i) if the instrument is available (or if the storage ring is down, perhaps), and (ii) if there are any deadlines coming up (like if the storage ring is about to be topped up). This can be used to pause data acquisition when the instrument is not available, for example. By default this object does nothing, but custom subclasses can handle any particular conditions at the beamline. |

snapshot |

An object which gathers a snaphot of the instrument prior to data acquisition, and passes this data to the recorders. By default captures the positions of all motors. |